Texas – A “traffic stop” for the purpose of issuing a “transportation” citations will almost ALWAYS lack reasonable suspicion and articulable probable cause. And here is why….

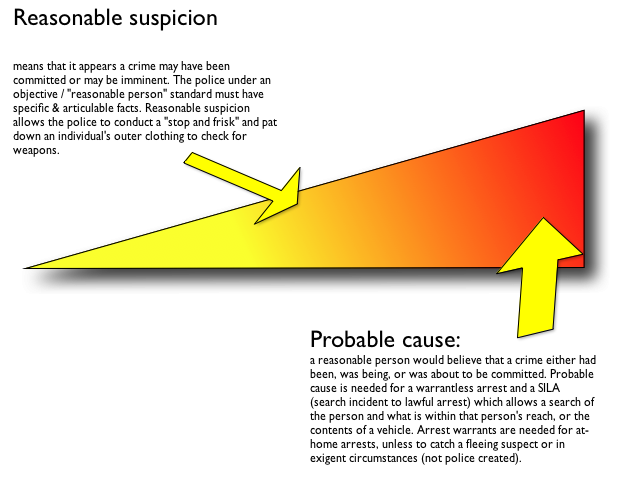

If an officer cannot articulate specific factual elements or produce prima facie evidence that an individual was or is actively engaged in “transportation,” then how is it possible for the officer to just skip over ‘reasonable suspicion’ and go directly to ‘probable cause’ to believe that a crime under the “transportation” code has actually been, is being, or is about to be, committed? Especially considering that such criminality is created and exists solely under a malum prohibitum statutory scheme that relates solely to regulating “transportation” and activities that are directly subordinate and ancillary thereto?

Upon what specific articulable facts must an officer first base ‘reasonable suspicion’ that an individual is engaging in “transportation” in order to reach the necessary level of ‘probable cause’ to allege criminal activity, for it is one thing to inherently understand that criminality exists when an act is itself morally wrong and unjustifiable, while also being readily identifiable as having harmed another individual or their property. Acts such as fraud, theft, assault, or murder are some examples of such acts.

However, in a malum prohibitum statutory scheme that is strictly regulatory in its general nature, such criminality is neither morally wrong nor necessarily unjustifiable, and, more often than not, involves no actual victim complaining of palpable injury to their person or property. Therefore, Respondent asserts that the common standard for ‘reasonable suspicion’ or ‘probable cause’ is not sufficient in such cases, in that the naked unsubstantiated claim of either would suffice to provide an officer with far more opportunity and latitude for abuse of his or her authority and in depriving individuals of their rights against unreasonable searches and seizures as well as due process. The result being that the defining elements necessary to make a malum prohibitum allegation of criminality now rests solely in the subjective opinion and determinations of the officer alone, and not within the statutory scheme that defines and controls it.

And unlike other forms of malum prohibitum statutory schemes, such as possession of drugs or drug paraphernalia, where it is the possession itself that is the criminal act, and which requires at least some reasonable indicator or facts that the person was in possession of same, how is this to be accomplished when the act itself is simply regulatory and there are no articulable facts that lead to the Governing Subject Matter being regulated? How does an officer come to have ‘reasonable suspicion’ or ‘probable cause’ to suspect or believe that a regulatory offense that is completely ancillary and subordinate only to the regulated Governing Subject Matter of “transportation,” is being, has been, or is about to be committed, without any articulable facts or evidence that “transportation” was or is being engaged in?

For instance, how does an officer look at a family minivan traveling down the highway and reach the conclusion that the mother-of-three inside the van is actually a “carrier” secretly engaged in the business of transporting passengers, goods, or property from one place to another for compensation or hire? Even if an officer began with the premise that the minivan was ‘speeding,’ at what point is the officer required to actually investigate the existence of facts and evidence necessary to establish and prove that “transportation” is a factual element of the ancillary regulatory offense being alleged? Despite the fact that there actually is not any offense whatsoever that is defined as “speeding” within the “Transportation” Code, the presumption of such an offense is based entirely upon the statutes within that code as being a regulated activity subordinate and ancillary to the Governing Subject Matter of “transportation,” not just “speeding” in and of itself. “Speeding” is not the primary regulated subject matter, “transportation” is, hence, an individual can be “speeding” only if it can first be proven that they were actively engaged in “transportation” at the time of the alleged offense.

Which begs the question, is the officer, the prosecutor, and the court, allowed to simply presume the existence of “transportation” for the purpose of a criminal prosecution, even though there are no facts or evidence that this essential element of the offense even exists? Isn’t this lack of evidence for the existence of the primary element of the offense necessarily exculpatory[1] to the accused individual by default? Isn’t the prosecutor required as a matter of right and law to disclose that lack of evidence and dismiss the case rather than simply presuming the existence of “transportation” and seeking to prosecute anyway (see footnote 9 ibid)? Isn’t this prime element of the existence of “transportation” the sole basis for the court having jurisdiction of the matter in the first instance considering that the subordinate and ancillary regulatory offense is no crime at all without it?

In relation to an offense that is entirely malum prohibitum under a regulatory statute, how could an officer possibly get to ‘probable cause’ without actual knowledge and understanding of all the specific elements of the alleged offense codified by the statutory scheme? Does the officer need only one out of three statutory elements that have to be proven, or is it just four out of five, or perhaps seven out of ten? Is it possible that an officer cannot reach probable cause in such cases without being able to express facts proving the existence of all elements required to be proven, beginning with proof that “transportation” was being engaged in at the time of the alleged offense? And if not, then how is such a standard not entirely capricious, arbitrary and subjective, and, thus, completely unconstitutional in relation to an individual’s right of due process and to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures, not to mention the unreasonably increased danger to their property and/or person by overzealous or abusive public servants?

Respondent asserts that such ‘reasonable suspicion’ or ‘probable cause’ simply cannot be reasonably or objectively obtained in instances where an offense is defined and governed entirely by statutory schemes as a malum prohibitum offense using the present standards established by the courts when applied to the private “non-transportation” activities of the general public.

Footnotes:

[1] Art. 2.01. DUTIES OF DISTRICT ATTORNEYS. Each district attorney shall represent the State in all criminal cases in the district courts of his district and in appeals therefrom, except in cases where he has been, before his election, employed adversely. When any criminal proceeding is had before an examining court in his district or before a judge upon habeas corpus, and he is notified of the same, and is at the time within his district, he shall represent the State therein, unless prevented by other official duties. It shall be the primary duty of all prosecuting attorneys, including any special prosecutors, not to convict, but to see that justice is done. They shall not suppress facts or secrete witnesses capable of establishing the innocence of the accused.

Leave a Reply to Timothy Jenkins Cancel reply